Drangsal – Harieschaim

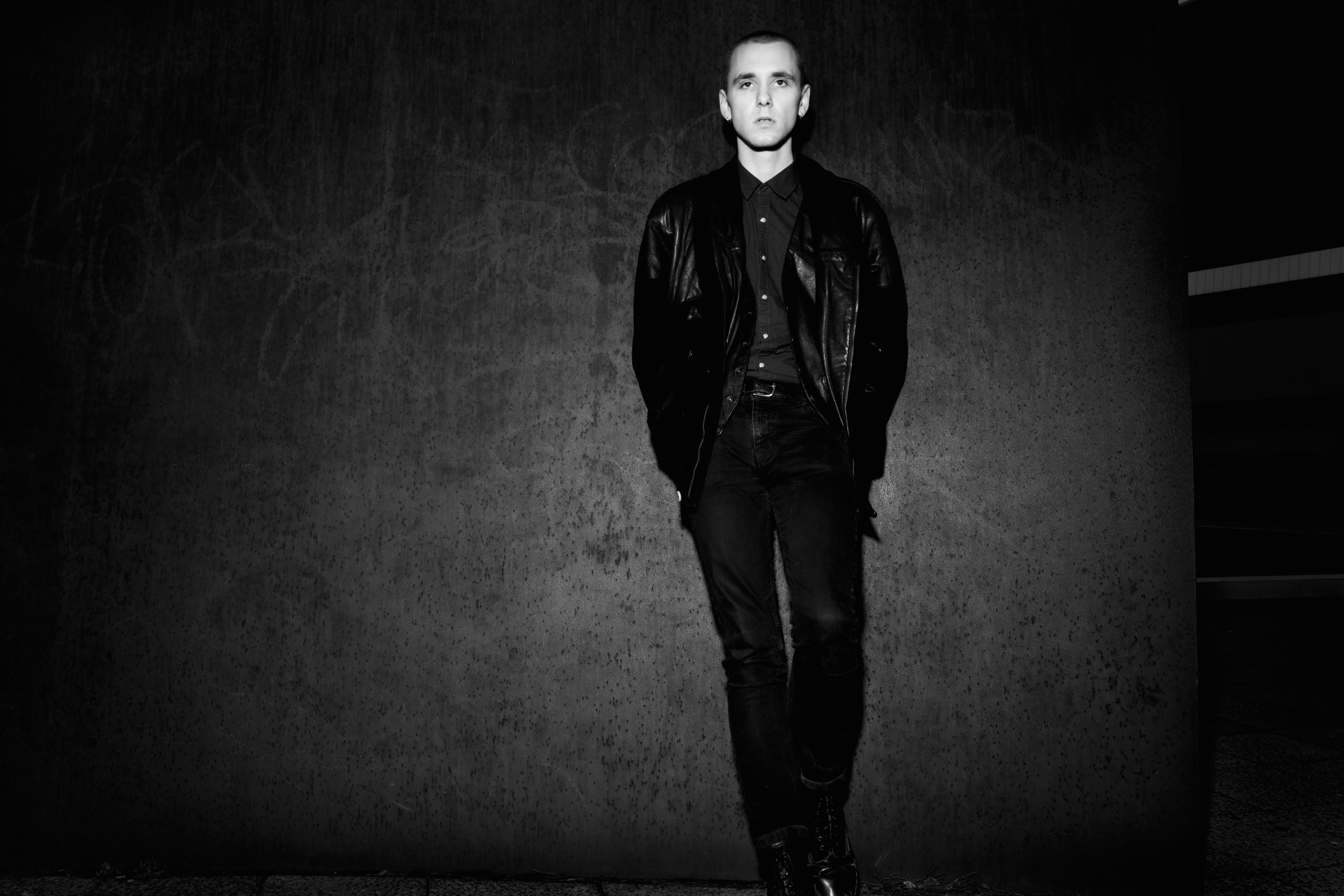

Max Gruber ist Drangsal, wobei Mensch und Kunstfigur so nervös sind, dass sie in ihrer Unruhe verschmelzen. Max schläft kaum, arbeitet rastlos an seiner Musik, am Tag und in der Nacht. Er träumt nicht, seine Tage aber sind gesättigt von Fantasien. „Seid lieb zu uns, wir sind noch Kinder“ erbittet der zu gleichen Teilen zart wie brutal besaitete Mastermind ins Mikrofon. Das Konzert ist ausverkauft – und die Leute sind nicht nur lieb, sie sind euphorisch! Obwohl es bisher nur ein paar Demos zu hören gibt. Dieser junge Mensch besitzt eine Anziehungskraft, soviel ist klar, sein Wesen verspricht Spektakel, sein Auftreten hält es ein. Harieschaim, das erste Album des 22-jährigen, ist eine dichte Aneinanderreihung von schnellen, aufgeregten Popsongs – sagen wir: Popwunder? –, keine Atempause, das Referenzjahrzehnt 80er-Jahre wird erschöpft und durchbrochen. Harieschaim, heute Herxheim, ist auch ein merkwürdiges Dorf, Max’ Geburtsort genaugenommen. Nirgendwo in Deutschland hat es so lange Kannibalismus gegeben, im nahegelegenen Hinterkaifeck wurde 1922 eine ganze Großfamilie ermordet, natürlich entfernte Verwandte aus Max’ Stammbaum. Doch in Herxheim fing alles an: Sein Vater war da Gastwirt, nahm Mixtapes für die Kneipe auf, spielte sie seinem Jungen im Auto vor. Das Kind verfiel so sehr der oft englischen Musik, dass es sich fortan zweisprachig ausdrückte. Eine popkulturelle Kindheit. Mit 5 Jahren schaute Max mit seinen Eltern MTV, verlor sich in Marylin Mansons The Dope Show. Von da an wusste er: Ich will auch irgendwie so etwas werden. Ein Weirdo. Spätestens in der Pubertät stellte er fest, ohnehin einer zu sein. Man könnte aber auch sagen: ein Charakter! Nun galt es für den jungen Entschlossenen, Formen für sein diffuses Wesen zu finden. Und das in einem erzkatholischen Dorf bei Landau! Max ging durch eine harte Schule: „Entweder ich lasse mich in der Pause verkloppen, oder ich lackiere mir die Fingernägel in einer noch auffälligeren Farbe.“

Max Gruber ist Drangsal, wobei Mensch und Kunstfigur so nervös sind, dass sie in ihrer Unruhe verschmelzen. Max schläft kaum, arbeitet rastlos an seiner Musik, am Tag und in der Nacht. Er träumt nicht, seine Tage aber sind gesättigt von Fantasien. „Seid lieb zu uns, wir sind noch Kinder“ erbittet der zu gleichen Teilen zart wie brutal besaitete Mastermind ins Mikrofon. Das Konzert ist ausverkauft – und die Leute sind nicht nur lieb, sie sind euphorisch! Obwohl es bisher nur ein paar Demos zu hören gibt. Dieser junge Mensch besitzt eine Anziehungskraft, soviel ist klar, sein Wesen verspricht Spektakel, sein Auftreten hält es ein. Harieschaim, das erste Album des 22-jährigen, ist eine dichte Aneinanderreihung von schnellen, aufgeregten Popsongs – sagen wir: Popwunder? –, keine Atempause, das Referenzjahrzehnt 80er-Jahre wird erschöpft und durchbrochen. Harieschaim, heute Herxheim, ist auch ein merkwürdiges Dorf, Max’ Geburtsort genaugenommen. Nirgendwo in Deutschland hat es so lange Kannibalismus gegeben, im nahegelegenen Hinterkaifeck wurde 1922 eine ganze Großfamilie ermordet, natürlich entfernte Verwandte aus Max’ Stammbaum. Doch in Herxheim fing alles an: Sein Vater war da Gastwirt, nahm Mixtapes für die Kneipe auf, spielte sie seinem Jungen im Auto vor. Das Kind verfiel so sehr der oft englischen Musik, dass es sich fortan zweisprachig ausdrückte. Eine popkulturelle Kindheit. Mit 5 Jahren schaute Max mit seinen Eltern MTV, verlor sich in Marylin Mansons The Dope Show. Von da an wusste er: Ich will auch irgendwie so etwas werden. Ein Weirdo. Spätestens in der Pubertät stellte er fest, ohnehin einer zu sein. Man könnte aber auch sagen: ein Charakter! Nun galt es für den jungen Entschlossenen, Formen für sein diffuses Wesen zu finden. Und das in einem erzkatholischen Dorf bei Landau! Max ging durch eine harte Schule: „Entweder ich lasse mich in der Pause verkloppen, oder ich lackiere mir die Fingernägel in einer noch auffälligeren Farbe.“

Diese  Schule jedenfalls hat seiner Kunst nicht geschadet, ebenso wenig wie sein autodidaktischer Lernprozess: „Mit 14 wusste ich dann: wenn ich Musik machen will, muss ich mir das aneignen.“ Und egal was er getan hat, für Herxheim war es zu krass. Also weg da: in Landau freundet er sich in ihren Anfangstagen mit Sizarr an, über Mannheim geht es nach Leipzig und Berlin, immer auf der Suche nach einem Ausdruck. Früh lernt er den späteren Hitproduzenten Markus Ganter kennen. Der ist da selbst noch ein unbeschriebenes Blatt, aber Max entscheidet: mit dem werde ich später arbeiten. Ein paar Jahre darauf ruft Ganter ihn an: Wollen wir jetzt dein Album machen? Max rastet aus. Es geht los. Seit seinen ersten Songs wird Max dabei von Ganters Erlkönig, Benjamin Griffey alias Casper, protegiert. Max hat ihm viel zu verdanken.

Schule jedenfalls hat seiner Kunst nicht geschadet, ebenso wenig wie sein autodidaktischer Lernprozess: „Mit 14 wusste ich dann: wenn ich Musik machen will, muss ich mir das aneignen.“ Und egal was er getan hat, für Herxheim war es zu krass. Also weg da: in Landau freundet er sich in ihren Anfangstagen mit Sizarr an, über Mannheim geht es nach Leipzig und Berlin, immer auf der Suche nach einem Ausdruck. Früh lernt er den späteren Hitproduzenten Markus Ganter kennen. Der ist da selbst noch ein unbeschriebenes Blatt, aber Max entscheidet: mit dem werde ich später arbeiten. Ein paar Jahre darauf ruft Ganter ihn an: Wollen wir jetzt dein Album machen? Max rastet aus. Es geht los. Seit seinen ersten Songs wird Max dabei von Ganters Erlkönig, Benjamin Griffey alias Casper, protegiert. Max hat ihm viel zu verdanken.

Auch wenn in dieser Biografie manchmal die Rede von Fügung sein könnte, ist sie durchaus troubled, hat Spuren hinterlassen. Zum Beispiel auf der von Tattoos gezeichneten Haut, die von Max’ Besessenheit gegenüber exzentrischen Industrial-Protagonisten oder dem Abseitigen per se erzählt. Hier finden wir eine Seele, die die Dunkelheit kennt! So ist es durchaus bemerkenswert, wie eingängig, weltgewandt und freundlich die zehn Songs auf Hariescheim daherkommen. Man könnte gar behaupten, in der Musik des Max Gruber kreuzten sich gleich mehrere Widersprüche! Und wenn es so viel Abgrund gibt, warum meint man dann beim Hören, Max wolle die ganze Welt umarmen? „Wenn ich das, was in mir vorgeht, auf der Straße erzählen würde, hätte ich Probleme – wenn ich aber davon singe, tanzen die Leute. Und am Ende des Tages will ich den Menschen eben lieber etwas geben, über das sie sich freuen können, als dass es ihnen schadet. So als ob ich all das Schlechte in ein Rohr stecke und am anderen Ende kommt etwas heraus, das den Leuten gefällt – das finde ich einen schönen Gedanken.“ Wie in der Idee des Wolpertingers, nach dem er auch einen Song benannt hat, funktioniert sein Prinzip: All das, was er sein will und doch nicht bedeuten kann (weil es das nicht gibt), nimmt er auseinander, setzt es zusammen, formt es zu einem und wird zu diesem Wesen, das den Widerspruch nicht nur in sich trägt, sondern stolz nach außen zeigt.

Dann purzelt Max noch ein Satz aus dem Mund, der so ziemlich alles sagt: »Musik ist oft ein Substitut für Tränen, ich will am Ende aber lieber Lachen als Weinen.« Seine Musik – vom Jugendzimmer bis auf die großen Bühnen – lädt ein, dabei mitzumachen. Und so findet Max Gruber zum Leben und seine Musik zur Welt! –Hendrik Otremba

Max Gruber is Drangsal, though the man and his persona are so nervous that their turmoil makes them melt into one. Max rarely sleeps, he works restlessly on his music, day and night. He doesn’t dream, but his days are satiate with fantasies. “Seid lieb zu uns, wir sind noch Kinder” –Be kind to us, we are only children–, pleads the mastermind into his microphone, at once delicate and brutal at heart. The concert is sold out – and the crowd is not just kind, they are euphoric. Even though there are only a few demos so far. This young guy has got charm, that’s for sure – his entrance promises a spectacle, and his energy lives up to that. Harieschaim, the 22-year-old’s first album, is a succession of fast, pumped pop songs – let’s say: a pop prodigy? –, no breathing space, the referential decade of the 80s gets run down and broken.

though the man and his persona are so nervous that their turmoil makes them melt into one. Max rarely sleeps, he works restlessly on his music, day and night. He doesn’t dream, but his days are satiate with fantasies. “Seid lieb zu uns, wir sind noch Kinder” –Be kind to us, we are only children–, pleads the mastermind into his microphone, at once delicate and brutal at heart. The concert is sold out – and the crowd is not just kind, they are euphoric. Even though there are only a few demos so far. This young guy has got charm, that’s for sure – his entrance promises a spectacle, and his energy lives up to that. Harieschaim, the 22-year-old’s first album, is a succession of fast, pumped pop songs – let’s say: a pop prodigy? –, no breathing space, the referential decade of the 80s gets run down and broken.

Harieschaim, today’s Herxheim, is a strange village too – Max’s birth place, to be exact. Nowhere else in Germany has cannibalism existed as long as here, in the nearby place Hinterkaifeck an entire family was murdered, naturally distant relatives from Max’s family tree. But Herxheim is where it all began: His father owned a pub, recorded mixtapes for it, played them to his boy in the car. The child became so addicted to the often English music that he would soon express himself bilingually. A popcultural childhood. At age 5 Max watched MTV with his parents, got lost in Marilyn Manson’s The Dope Show. That was when he knew: I want to be something like that, somehow. A weirdo. At least when puberty had hit, he realised he already was one. But you might just as well call him a character. Now it was up to the determined youngster to find shapes for his diffuse being. And all of that in a little village in Germany’s deeply Catholic southwest! It was a school of hard knocks for Max: “Either I’ll let them beat me up in the break, or I’ll paint my fingernails an even brighter colour”.

At least this school has done no harm to his art. Neither has his autodidactic process of learning: “At 14 I realised: If I want to make music, I have to pick up on this.” And no matter what he did, for Herxheim it would be too mad. So he leaves: In Landau he befriends Sizarr during their early days, moves through Mannheim to Leipzig and Berlin, always hunting for a way of expression. Early on he meets the later hit producer Markus Ganter. Back then Ganter is still a blank page himself, but Max decides: this is the guy I’m going to work with someday. A few years later Ganter gives him a call: How about we make your album now? Max loses it. This thing is going off. Ever since the first songs, Max is supported by Ganter’s flagship, Benjamin Griffey alias Casper. Max owes him a lot.

Although there are points in this biography where one could call it fate, it is a troubled one at the same time, and left its traces. For instance on the tattoo-lined skin telling stories of Max’s obsession with eccentric industrial protagonists or the obscure per se. This is where we meet a soul that knows darkness – and yet the ten songs on Harieschaim appear remarkably catchy, sophisticated and friendly. One might even claim that several contradictions meet at once in the music of Max Gruber. And if there is so much abyss, then why does listening to it feel as if Max wanted to embrace the whole world? “If I told people on the street about what’s going on inside me, I’d have issues – but when I sing about it, it makes people dance. And at the end of the day I’d rather give them something to be happy about than something that harms them. It’s as if I put all the bad stuff into a tube and what comes out on the other end is something that people like – that’s seems like a nice thought to me.” His principle works like the idea of the Wolpertinger, the cross-breed creature from Bavarian mythology which he named a song after: All the things he wants to be, but can’t represent (because they don’t exist), he takes them apart, shapes them into one and becomes this being, who doesn’t only carry the contradiction within himself but proudly wears it on his sleeve.

Although there are points in this biography where one could call it fate, it is a troubled one at the same time, and left its traces. For instance on the tattoo-lined skin telling stories of Max’s obsession with eccentric industrial protagonists or the obscure per se. This is where we meet a soul that knows darkness – and yet the ten songs on Harieschaim appear remarkably catchy, sophisticated and friendly. One might even claim that several contradictions meet at once in the music of Max Gruber. And if there is so much abyss, then why does listening to it feel as if Max wanted to embrace the whole world? “If I told people on the street about what’s going on inside me, I’d have issues – but when I sing about it, it makes people dance. And at the end of the day I’d rather give them something to be happy about than something that harms them. It’s as if I put all the bad stuff into a tube and what comes out on the other end is something that people like – that’s seems like a nice thought to me.” His principle works like the idea of the Wolpertinger, the cross-breed creature from Bavarian mythology which he named a song after: All the things he wants to be, but can’t represent (because they don’t exist), he takes them apart, shapes them into one and becomes this being, who doesn’t only carry the contradiction within himself but proudly wears it on his sleeve.

Then another sentence tumbles out of Max’s mouth and pretty much says it all: “Music is often a substitute for tears, but in the end I’d rather laugh than cry.” His music – from his teenage bedroom to the big stage – sends out an invitation to join in. And this is how Max Gruber arrives at life and brings his music into the world!